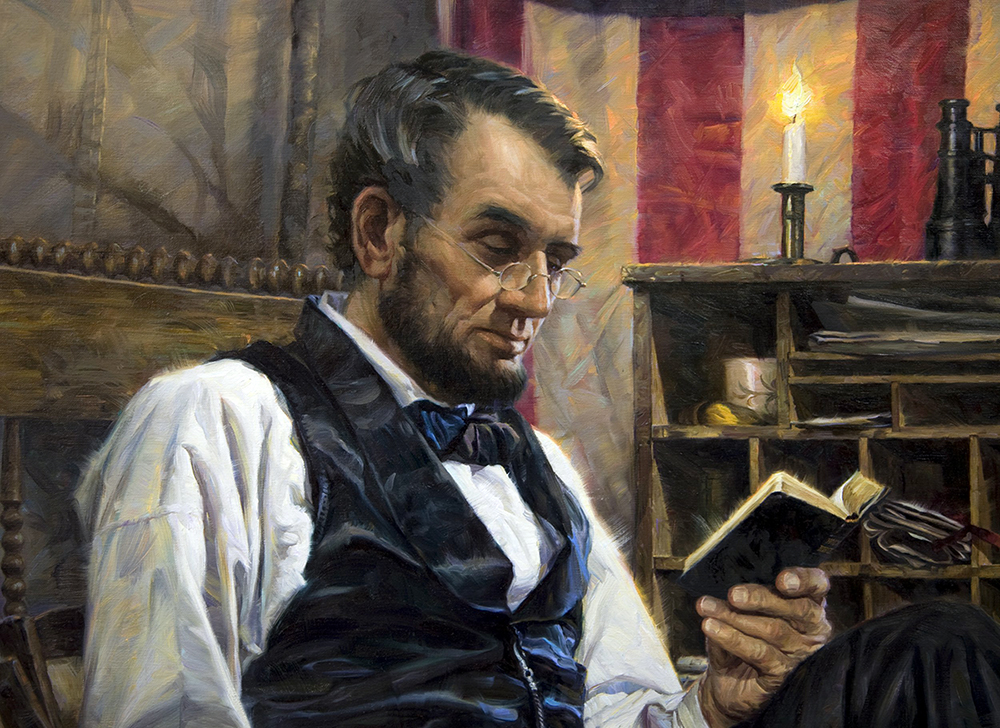

Lincoln at Antietam October 3, 1862 “In The Darkest Hour”

“I have felt His hand upon me in great trials and submitted to His guidance.” Abraham Lincoln

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

November 19, 1863

On June 1, 1865, Senator Charles Sumner referred to the most famous speech ever given by President Abraham Lincoln. In his eulogy on the slain president, he called the Gettysburg Address a “monumental act.” He said Lincoln was mistaken that “the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here.” Rather, the Bostonian remarked, “The world noted at once what he said, and will never cease to remember it. The battle itself was less important than the speech.”

While he may have had the intention to elevate the importance of the speech, the Senator, in his faulty rationalization, completely missed the point that people live to write speeches because battles are fought and won. Words fall short when it comes to conveying the depth of the meaning of the sacred deaths of those who offer up their lives to fight for a noble cause, which is part of the very core idea of Lincoln’s speech.

There are five known copies of the speech in Lincoln’s handwriting, each with a slightly different text, and named for the people who first received them: Nicolay, Hay, Everett, Bancroft and Bliss. Two copies apparently were written before delivering the speech, one of which probably was the reading copy. The remaining ones were produced months later for soldier benefit events. Despite widely-circulated stories to the contrary, the president did not dash off a copy aboard a train to Gettysburg. Lincoln carefully prepared his major speeches in advance; his steady, even script in every manuscript is consistent with a firm writing surface, not the notoriously bumpy Civil War-era trains. Additional versions of the speech appeared in newspapers of the era, feeding modern-day confusion about the authoritative text.

Bliss Copy

Ever since Lincoln wrote it in 1864, this version has been the most often reproduced, notably on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. It is named after Colonel Alexander Bliss, stepson of historian George Bancroft. Bancroft asked President Lincoln for a copy to use as a fundraiser for soldiers (see “Bancroft Copy” below). However, because Lincoln wrote on both sides of the paper, the speech could not be reprinted, so Lincoln made another copy at Bliss’s request. It is the last known copy written by Lincoln and the only one signed and dated by him. Today it is on display at the Lincoln Room of the White House.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Abraham Lincoln

November 19, 1863

Nicolay Copy

Named for John G. Nicolay, President Lincoln’s personal secretary, this is considered the “first draft” of the speech, begun in Washington on White house stationery. The second page is written on different paper stock, indicating it was finished in Gettysburg before the cemetery dedication began. Lincoln gave this draft to Nicolay, who went to Gettysburg with Lincoln and witnessed the speech. The Library of Congress owns this manuscript.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle field of that war. We come to dedicate a portion of it, as a final resting place for those who died here, that the nation might live. This we may, in all propriety do.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate we can not consecrate we can not hallow, this ground The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have hallowed it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here; while it can never forget what they did here.

It is rather for us, the living, we here be dedicated to the great task remaining before us that, from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here, gave the last full measure of devotion that we here highly resolve these dead shall not have died in vain; that the nation, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Hay Copy

Believed to be the second draft of the speech, President Lincoln gave this copy to John Hay, a White House assistant. Hay accompanied Lincoln to Gettysburg and briefly referred to the speech in his diary: “the President, in a fine, free way, with more grace than is his wont, said his half dozen words of consecration.” The Hay copy, which includes Lincoln’s handwritten changes, also is owned by the Library of Congress.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met here on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But in a larger sense, we can not dedicate we can not consecrate we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but can never forget what they did here.

It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they have, thus far, so nobly carried on. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation shall have a new birth of freedom; and that this government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Everett Copy

Edward Everett, the chief speaker at the Gettysburg cemetery dedication, clearly admired Lincoln’s remarks and wrote to him the next day saying, “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.” In 1864 Everett asked Lincoln for a copy of the speech to benefit Union soldiers, making it the third manuscript copy. Eventually the state of Illinois acquired it, where it’s preserved at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here, have, thus far, so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Bancroft Copy

As noted above, historian George Bancroft asked President Lincoln for a copy to use as a fundraiser for soldiers. When Lincoln sent his copy on February 29, 1864, he used both sides of the paper, rendering the manuscript useless for lithographic engraving. So Bancroft kept this copy and Lincoln had to produce an additional one (Bliss Copy). The Bancroft copy is now owned by Cornell University.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Source for all versions: Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Roy P. Basler and others. | Lincoln speech text is in the public domain; the organization, remaining text, and photo on this page are copyright 2017 Abraham Lincoln Online.